Who were the Hebrews?

The first person mentioned in the Bible as a “Hebrew” is Abraham[1].

“One who had escaped came and reported this to Abram the Hebrew.” (Genesis 14:13)

Is Abraham the first Hebrew? The Hebrew word for “Hebrew” is עברי / eevriy[2] and comes from the root word עבר / avar, which means, “to cross over.” A Hebrew is “one who has crossed over.” One of Abraham's ancestors was Eber[3] (עבר).

The name Eber also comes from the same root אבר / avar, making it possible that Eber was also a “Hebrew.” The Bible is the story of God and his covenant relationship (Hebraicly understood as “crossing over” from death to life) with an ancestral line beginning with Adam through his descendants Noah, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Jacob's descendants, who became the “nation of Israel” also known as “the Hebrews.” A Hebrew was one who had “crossed over” into a covenant relationship with God, beginning with Adam. Any references to the “Ancient Hebrews” in this book, is referring to the ancestral line from Adam to the Nation of Israel.

The Origin of the Hebrew Language and Alphabet

Prior to the incident of the Tower of Babel, which will be discussed later, only one language existed;

“And the whole earth was of one language, and of one speech.” (Genesis 11:1)

From this we can conclude that God, Adam and Eve and their descendants spoke Hebrew.

The first use of the Hebrew language is recorded in Genesis 1:3 where God says, יהי אור (yehiy or), meaning, “light exist.” In the creation account God gave Hebrew names to the sky (shamayim), land (erets), sun (shemesh), moon (yerey'ach), stars (kokhaviym) and man (adam). When God formed Adam he gave him this spoken language and communicated with him (Genesis 1:28). The man also used this same language to give names[4] to all of the birds (oph), animals (behemah), beasts (hayah tsadeh) and woman[5] (iyshah).

The first indication of writing is found in Genesis 4:15 where God puts a “mark” on Cain. The Hebrew word for “mark” is אות / owt and is also the Hebrew word for a “letter” indicating that it may have been a “letter” that God placed on him.

As will be demonstrated later, the Ancient Hebrew language (speech) and alphabet (script) are dependent upon each other, supporting a simultaneous appearance of the language and alphabet. Since God is the originator of the Hebrew language, he is also the originator of the alphabet.

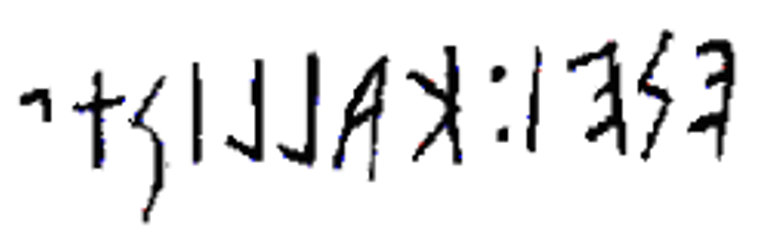

Pre-flood writings have been discovered in the city of Kish[6] (fig. 1). Several of the letters in this tablet are identical to the original Hebrew letters[7] (See Appendix D).

Figure 1 Pre-flood pictograph found in the pre-flood city of Kish.

Genesis chapter 5 gives a genealogical record from Adam to Noah where we find that all the names are Hebrew. We know that these names are Hebrew rather than another language because all of the names have meaning only in Hebrew and are related to their character as described in the Biblical text. For instance, the Hebrew name Adam means “man” and he was the first “man.” Methuselah means “his death brings” and the flood came in the year that he died. Noah means “comfort” as he will bring comfort to his people[8].

Noah had three sons, Shem, Ham and Japheth. It is during their lives that God brought the great flood[9] because of man's wickedness. Only Noah and his family were spared. God commanded Noah and his descendants to:

“be fruitful and increase in number and fill the earth” (Genesis 9:1)

Noah's descendants remained in the area known as Mesopotamia[10]. Here man began to build the “Tower of Babel.” In order to cause the descendants of Noah to scatter and fill the earth, God said, “let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech”[11].

After the incident of the Tower of Babel, which occurred around 4,000 BCE[12], we find three major languages, each very different and unrelated to each other[13]; Egyptian, Sumerian and Hebrew. The arrival of the Egyptian and Sumerian languages seems to have mysteriously appeared out of nowhere. It is interesting to note that while all three have a very similar pictographic[14] form of writing, the sounds for each of the letters are different, possibly indicating the method which God used to confuse the language of men.

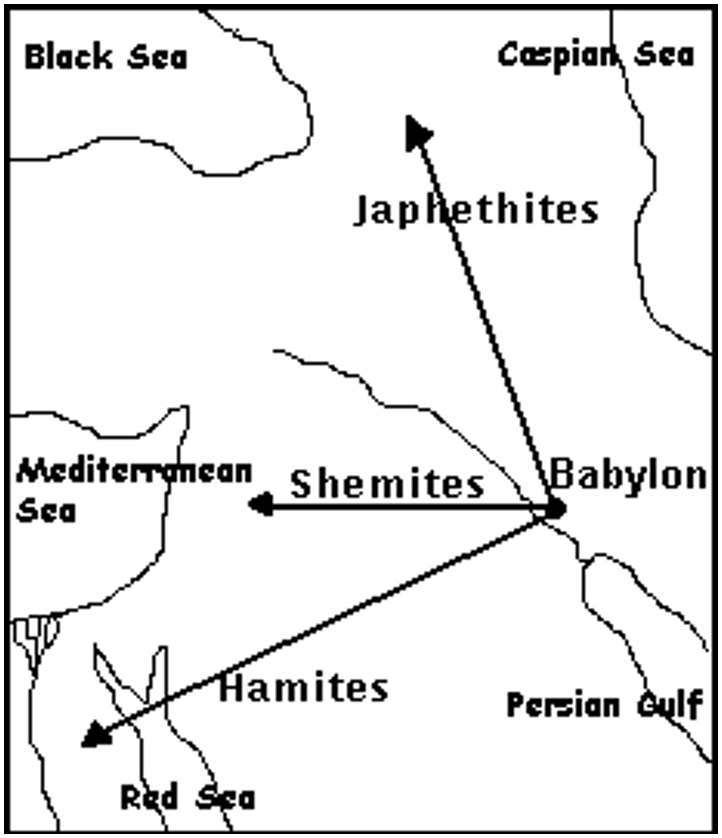

As a result of the Tower of Babel man began to migrate in three different directions from Mesopotamia, just as God planned (fig. 2). The Shemites[15] were the descendants of Shem, traveling west speaking Hebrew. The Hamites traveled south into Africa and became the Egyptians speaking Egyptian. The Japhethites traveled north becoming the Sumerians[16], probably a sub-group of the Scythians[17], speaking Sumerian. In Genesis 10 we find the “table of nations,” a record of the scattering of the descendants of the sons of Noah.

Figure 2 The scattering of the descendants of Noah's three sons.

It is not until we come to Noah's grand-children that we find names that are of a language other than Hebrew, such as Nimrod[18] (Genesis 11:8), Sabteca[19] (Genesis 10:7) and many others whose names have no meaning in Hebrew[20], correlating in time with the confounding of the language at the Tower of Babel.

It has long been a tradition within both Judaism and Christianity that Hebrew is the mother of all languages[21].

The evolution of the Hebrew alphabet

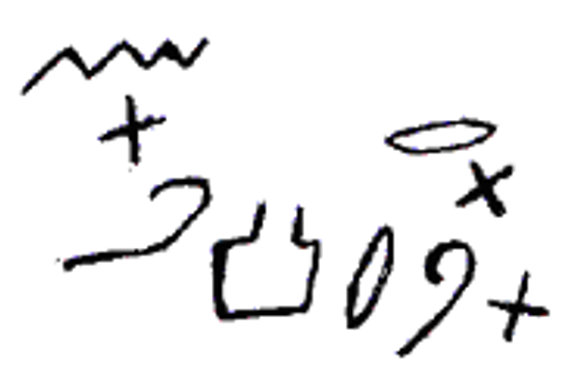

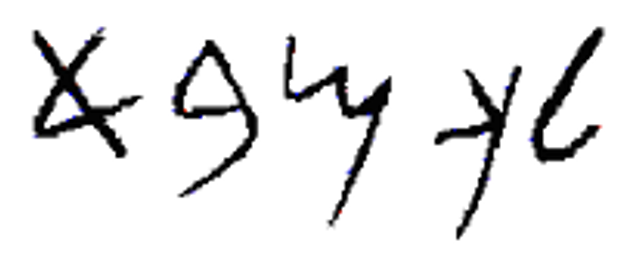

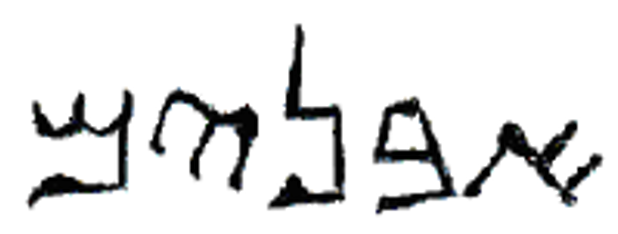

The original pictographic script (fig. 3) of the Ancient Hebrew alphabet[22] consisted of 22 letters, each representing an object such as water (top left corner) or a shepherd staff (second from right at bottom).

Figure 3 Ancient Shemitic/ Hebrew pictographic inscription on stone boulder c. 1500 BCE

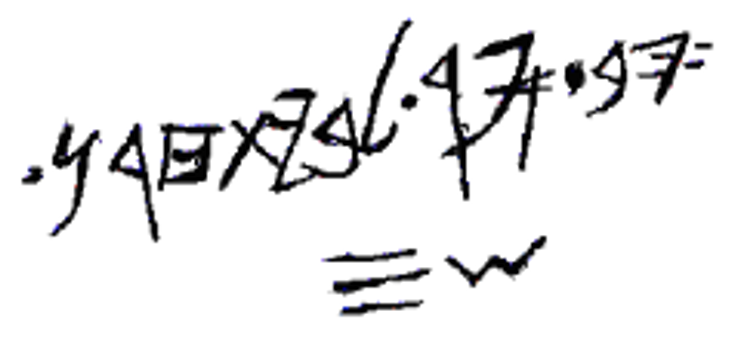

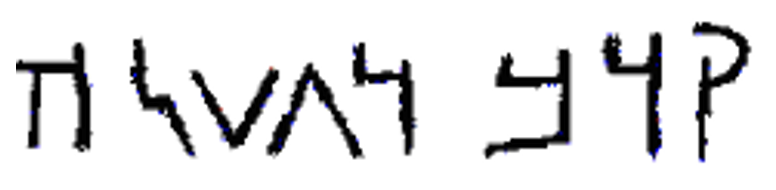

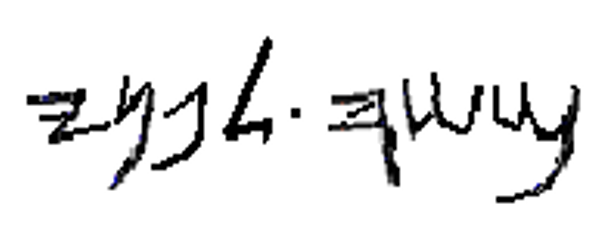

After the Tower of Babel, the Ancient Hebrew alphabet began to evolve into a simpler script (fig. 4) similar to the original pictographic alphabet.

Figure 4 Ancient Hebrew inscription on potsherd c. 900 BCE

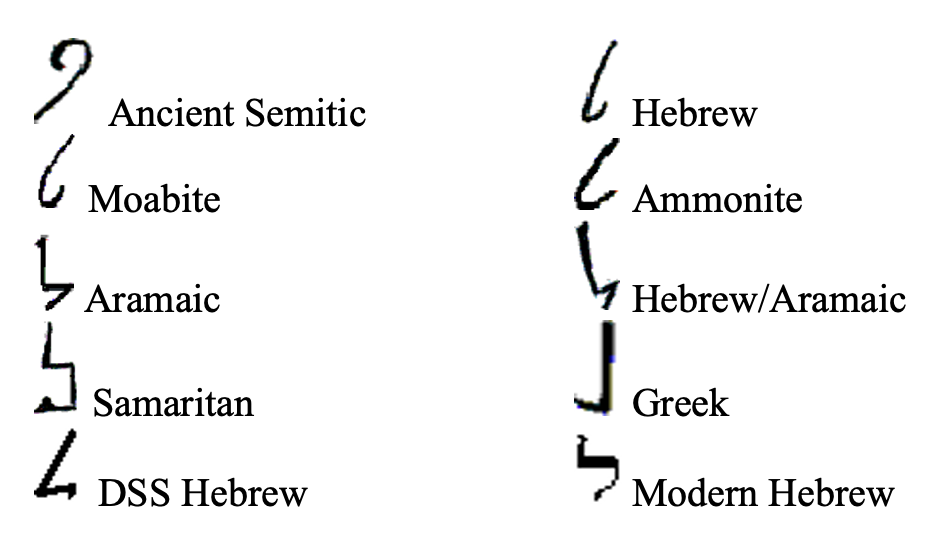

The Hebrews splintered into sub-groups such as the Phoenicians, Canaanites, Akkadians, Moabites (fig. 5), Ammonites (fig. 6), Arameans (fig. 8), and others, all known as Shemites. Due to the close proximity and interaction of these Shemitic cultures, their alphabet script evolved similarly.

Figure 5 Moabite inscription on stone c. 900 BCE

Figure 6 Ammonite inscription on stone c. 900 BCE

At other times, alphabet scripts evolved very differently. The most unique is the Ugaritic, consisting of 30 letters where the original pictographic script evolved into a cuneiform[23] script[24] (fig. 7) sometimes called Hebrew cuneiform.

Figure 7 Ugarit cuneiform inscription on clay tablet c. 1400 BCE

The Aramean script (Aramaic), used extensively in the Babylonian region, originated in the Hebrew script around 1000 BCE (fig. 8) and began to evolve independently of other Shemitic groups. By 400 BCE it no longer resembled the original pictographic script (fig. 9).

Figure 8 Aramaic inscription on stone incense altar c. 500 BCE

Figure 9 Aramaic inscription on stone plaque c. 20 CE.

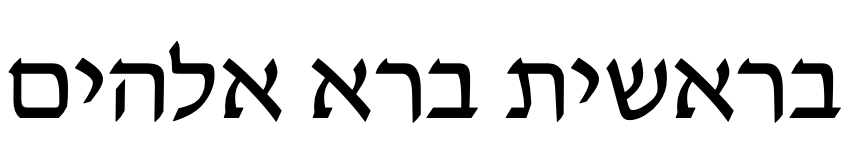

When the Hebrew people were taken into Babylonian captivity, they adopted the Aramaic script abandoning the Ancient Hebrew script. From this point to the present, the Hebrew language has been written in the Aramaic script (fig. 10).

Figure 10 Hebrew writings from the Dead Sea Scrolls c. 200 BCE

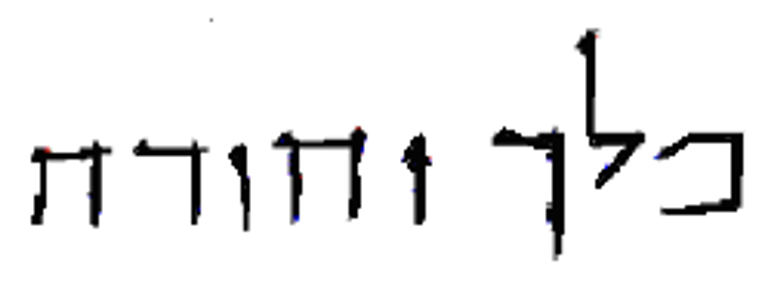

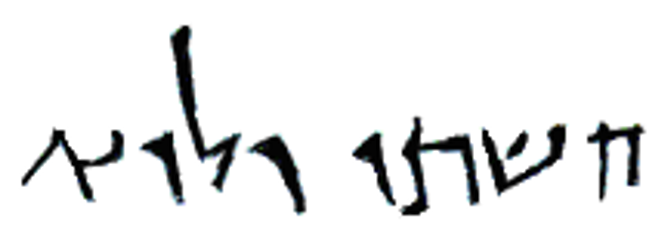

The Modern Hebrew script has remained very similar to the Hebrew of the first century BCE (fig. 11).

Figure 11 Modern Hebrew script from the Hebrew Bible.

While the majority of the Hebrew texts of the first century BCE and into the first century CE were written in the Aramaic script, the Ancient Hebrew pictographic script was not lost and was still used on occasion. The coins of this era used the Ancient pictographic Hebrew script as well as some scrolls such as those found in the Dead Sea caves (fig. 12).

Figure 12 Pictographic Hebrew writings from the Dead Sea Scrolls c. 100 BCE

The Samaritans lived in the land of Samaria, a region of Israel, at the time of Israel's captivity; they were not taken into Babylon with Israel. As a result of their isolation they are the only culture to retain a script (fig. 13) similar to the Ancient Hebrew script and is still used to this day.

Figure 13 Samaritan scripts

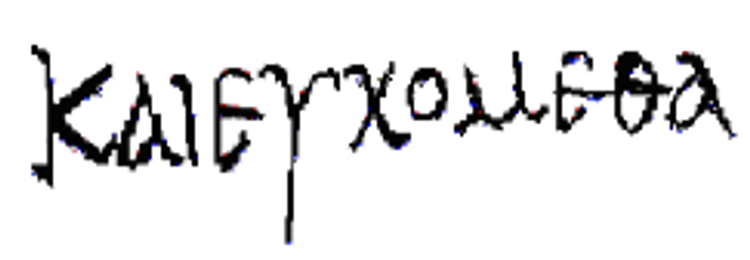

Around 1000 BCE, the Greeks adopted the Ancient Hebrew script (fig. 14). This Ancient Greek alphabet began to evolve over the centuries to become the Greek script (fig. 15) used today. While all the Shemitic scripts shown above were usually written from right to left, they were written from left to right at times[25]. The directions of the letters reveal the direction of writing. For example, figure 14 was written from right to left. Note the direction of the “E” (first letter from the right) and the “K” (fifth letter from the right). Compare these with the same letters in figure 15, which is written from left to right. Note the “K” (first letter from the left) and the “E” (fourth letter from the left). Around 500 BCE the Greeks finalized a left to right form of writing while the Shemites finalized a right to left form of writing.

Figure 14 Greek inscription found on bowl c. 800 BCE

Figure 15 Greek writing on New Testament papyrus c. 200 CE

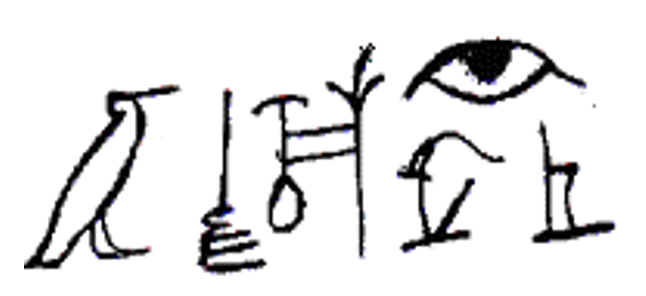

To the south of the Shemitic peoples, the Egyptians were writing with an alphabet almost identical to the Ancient Hebrew script. In addition to the alphabet, the Egyptians used a complex system of pictographs called hieroglyphs (fig. 16) where each pictograph represented one, two or three syllables.

Figure 16 Egyptian Hieroglyphs from the Book of the Dead c. 1350 BCE

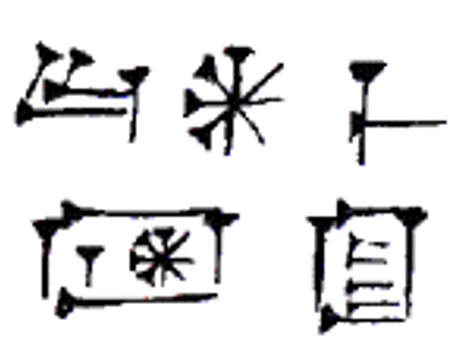

To the east of the Shemites were the Sumerians whose system of writing was very similar to the Egyptian with several hundred pictographs (fig. 17). Over time, these pictographs evolved into a cuneiform script (fig. 18) similar to the Ugaritic.

Figure 17 Sumerian Pictograph on clay tablet c. 3000 BCE

Figure 18 Sumerian Cuneiform on clay tablet c. 2500 BCE

Due to the common origin of all the scripts above, similarities of the script of different cultures can be observed. One example is the letter “lamed” that can be seen in several of the inscriptions above, as well as noting its similarity to our “L.”

Since the Egyptian, Sumerian, Greek, Aramaic, Arabic, Hebrew and other Shemitic cultures have their origins in the Ancient Hebrew script, tracing their history and evolution is beneficial to reconstructing the original Ancient Hebrew script. Appendix “C” includes a set of two charts for each of the 22 Hebrew letters. One chart includes all the known scripts of 14 languages. The other is a flowchart showing the evolution of the letter through the centuries

Why study the Ancient Hebrew language and culture?

The Hebrew people, whose culture and lifestyle were very different than our own, wrote the Bible between 1,500 and 500 BCE.

When we read the Bible as a 21st Century American our culture and lifestyle often influence our interpretation of the words and phrases of the Bible. A word such as “rain” has the meaning; “the coming down of water from the clouds in the sky,” but the interpretation of the word rain will be influenced by the context of the culture. This is true even in our own culture where the word “rain” can be interpreted differently. If the local weather station forecasts a “rain” shower for tomorrow, different people will interpret the word “rain” in different ways, with a circumstantial biasness. The bride and groom who are prepared for an outdoor wedding view this news with a negative connotation, while to the farmer in the middle of a drought season, it has a positive connotation. To the Ancient Hebrew nomads the word “rain” was usually equated with “life” since without it, their very existence would not be possible.

Another example of the importance of understanding the cultural setting can be seen in the word “dinner.” To my grandparents and their generation, “dinner” was the main meal of the day eaten at noon and a light “supper” was eaten in the evening. Whereas today, dinner is the main meal eaten in the evening. There are countless examples in our own English language of how word meanings change over time according to the culture.

Many times our cultural influence will give a different definition to words that was not intended by the Biblical authors. For example the Bible speaks of keeping and breaking the commands of God. The words “keep” and “break” are usually interpreted as “obedience” and “disobedience.” But this is not the Ancient Hebraic meaning of these words.

The Hebrew word for “keep” is (שמר / shamar), which literally means “to guard, protect, and cherish” while the Hebrew word for “break” is פרר / parar and literally means “to trample underfoot.” The Ancient Hebrew understanding of these words is not about mechanical obedience and disobedience of his commands, but ones attitude towards them. Will you cherish his commands or throw them on the ground and walk on them?

A people's language is closely related to their culture and without an understanding of the Hebrew culture we cannot fully understand their language. To cross this cultural bridge, we need to understand the Ancient Hebrew culture, lifestyle and language.

How do we study the Ancient Hebrew language and culture?

Archeologists who uncover Ancient artifacts study the Ancient cultures. Anthropologists interpret these artifacts to determine the Ancient culture's way of life. Throughout the world there remain primitive cultures whose lifestyles have remained the same for thousands of years, providing us with a close up view of how these Ancient cultures lived. One of these groups is the desert nomad of the Middle East who still lives much the way Abraham did over 3,000 years ago. Linguists and etymologists study the ancient languages, opening the door to their manner of speech and alphabets. Many Ancient cultures have left ancient texts recording their thoughts and lifestyle. The most notable text of the Ancient Hebrews is of course the Bible.

When we combine and study the material provided by these fields of study, we open the door to the culture and lifestyle of Ancient cultures. By studying these resources we can better understand their words, which they have recorded in the Bible. The purpose of this book is to teach the relationship between the Hebrew language and the Hebrew culture, which will give us a deeper, more accurate, understanding of Biblical words.

[1] Known as Abram before God changed his name.

[2] The letter ב (beyt) is pronounced as a “b” when at the beginning of a word, and usually a “v” within a word.

[3] Genesis 11.16

[4] Genesis 2.19

[5] Genesis 2.23

[6] Henry H. Halley, Halley's Bible Handbook (Grand Rapids, Mi: Zondervan, 24th) 44-5.

[7] Over time all alphabets evolve. Therefore, it is possible for the writing system of Noah's day to differ from the alephbet given to Adam.

[8] See Genesis 5:29

[9] A literal flood that covered the whole earth. See The Genesis Flood by John C. Whitcomb and Henry M. Morris.

[10] A Greek word meaning “between (meso) rivers (potamia),” the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

[11] Genesis 11.7

[12] Merrill F. Unger, “Tower of Babel,” Unger's Bible Dictionary, 1977 ed.: 115. (BCE - Before the Common Era, equivalent to BC)

[13] J.I. Packer, Merril C. Tenney, William White, Jr., Nelson's Illustrated Encyclopedia of Bible Facts (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1995) 337; Unger, “Egypt,” 288.

[14] A word of Greek origin meaning picture-writing where a picture represented a sound or combination of sounds. The Sumerian pictographs evolved into the cuneiform (wedge-shaped) writing familiar to most people.

[15] The Shemites (also called Semites) are the Hebrews. Later cultures, such as the Phonecians, Canaanites, Akkadians, Moabites, Amonites and Arameans sprouted out of the Hebrews and are also part of the Shemitic family.

[16] The land of the Sumerians was known as Sumer, which is Shinar in the Bible (Genesis 10.10) also known as Babylonia. It is believed that the Japhethites traveled north the Black and Caspian seas and are the ancestors of the Sumerians. See Unger, “Scythian,” 987 and Madelene S. Miller and J. Lane Miller, “Sumer,” Harper's Bible Dictionary, 1973 ed.: 710.

[17] Unger, “Scythian,” 987.

[18] See Strong's #5248

[19] See Strong's #5455

[20] The construction of Hebrew words, including names, follows a set of patterns. Words that do not follow these patterns are suspect of being of foreign origin.

[21] Will Smith, “Hebrew Language,” Smith's Bible Dictionary, 1948 ed.: 238.

[22] Also known as “Shemitic,” Semitic” “proto-siniatic,” proto-canaanite” and “paleo-hebrew.”

[23] Cuneiform, meaning, “wedge-shape,” is written with a stylus that is pressed into a clay tablet to form the letters.

[24] Because the Ugarit language is so similar to Hebrew, the Ugarit cuneiform is called Hebrew cuneiform.

[25] Ancient inscriptions were often written on stone using a hammer and chisel. Since the hammer was held in the right hand and the chisel in the left hand, a right to left writing was natural. When ink began to be used, it was preferable to write from left to right so that the hand would not smear the ink.