History of the Hebrew Bible

The following is an excerpt from Mr. Benner’s book, A Cultural and Linguistic Excavation of the Bible.

The Original Manuscripts

The original manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible, which would have been handwritten on animal skins or papyrus, have long since deteriorated. What remain today are copies from these original autographs.

In this digital age, electronic copies are perfect representations of the original. However, in ancient times copying a manuscript was a much more tedious labor and not as precise, allowing for human intervention or error.

Oldest Known Copies of Biblical Texts

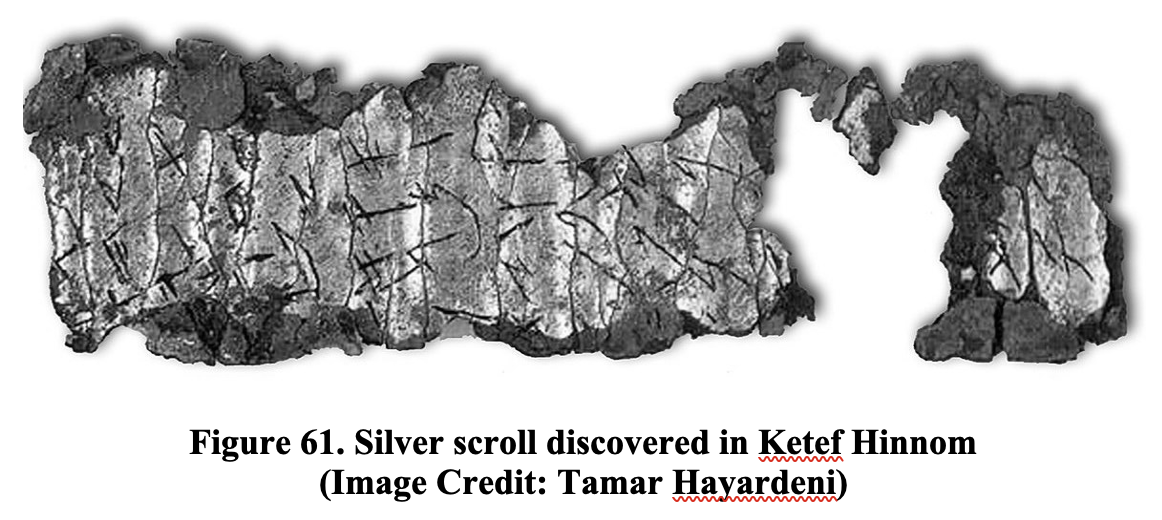

The oldest text of the Hebrew Bible was discovered in a tomb at Ketef Hinnom (Figure 61) in Israel in 1979. The text, inscribed on a silver scroll in a Paleo-Hebrew script dating to the 7th century BC, is the Aaronic blessing, which begins, yeverekh’kha YHWH Vayishmarekha (May YHWH bless you and keep you).

Another very ancient fragment of the Hebrew Bible is the Nash Papyrus (Figure 62) discovered in Egypt in 1898. The fragment includes the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:2-17) and the Sh’ma (Deuteronomy 6:4) and is dated to the 2nd century BC.

Very few ancient texts of the Hebrew Bible had been found and were very rare prior to 1947, when a depository of scrolls in the Dead Sea Caves provided us with a library of ancient manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible.

The Dead Sea Scrolls

As has been mentioned before, between 1947 and 1956 ancient scrolls and fragments of the Hebrew Bible were discovered in caves near the Dead Sea dating to the 1st century BC and the 1st century AD.

The manuscripts in the form of scrolls discovered in the Dead Sea Caves included all of the canonical books of the Hebrew Bible[1], as well as non-canonical books such as Enoch, Jubilees, Tobit, Sirach and psalms that are not part of the canonical 150 Psalms. Also found among the Dead Sea Scrolls were sectarian books such as the Community Rule, the War Scroll, the Damascus Document and commentaries on books of the Bible.

There are several different theories as to the origin of these texts.

The predominating theory asserts that the scrolls were the work of a Jewish sect called the Essenes. It is believed that the Essenes had resided in nearby Qumran, and they hid the scrolls in the near-by caves to protect them from the advancing Roman army.

Other possible theories for the creators of the scrolls include early Messianics (Christians) or Zadokite priests.

A newer theory and one ascribed to by the author is that the scrolls were old and unusable scrolls from various libraries and synagogues in Israel that were taken to the caves near Qumran for burial. In Jewish tradition, any document containing the name YHWH must be buried and may not be destroyed, burned or discarded. Supporting this theory is the fact that the only book not yet discovered in the caves is the book of Esther, which happens to be the only book of the Bible that does not contain the name YHWH, and therefore, would not be required to be buried.

The Isaiah Scroll

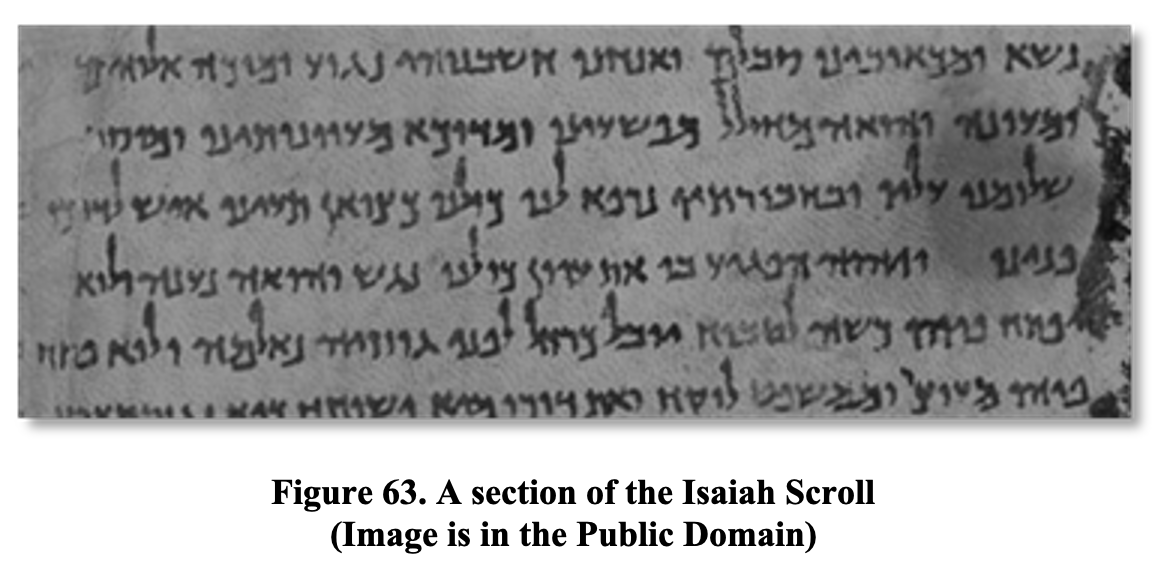

The most famous of the scrolls found within the Dead Sea Caves is the Isaiah Scroll (Figure 63).

While most of the scrolls are fragments, deteriorating or incomplete, the Isaiah Scroll is the single complete scroll found.

The life of a scroll depends on its handling and storage, but it can be used within a community for up to several hundred years. Some Torah scrolls still in use in synagogues today are over 500 years old.

The Isaiah Scroll from the Dead Sea Caves has been dated to around 200 BC. Isaiah wrote his original scroll around 700 BC and it may have been in use until around 200 BC. This means that it is possible that the Isaiah Scroll from the Dead Sea Caves could easily be a copy made directly from Isaiah’s original scroll.

The Aleppo Codex

Until the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, the oldest existing complete Hebrew Bible was the Aleppo Codex (Figure 64), also called the Masoretic text, which was written in the 10th century AD, a thousand years after the Dead Sea Scrolls. For centuries, this text has been the foundation for Jewish and Christian translators.

The major difference between the Aleppo Codex and the Dead Sea Scrolls is the addition of the nikkudot to the Hebrew words found in the Aleppo Codex.

While the Masoretic text and the Dead Sea Scrolls were transcribed a thousand years apart, they are amazingly similar, proving that the copying methods employed by the Jewish scribes over the centuries were very sophisticated and successful. However, there are some differences. The majority of these differences are minor issues, such as differences in spelling and grammar, but some are much more complex.

Besides the addition of the nikkudot, other changes occurred in the Hebrew text after making copies of copies. One of those more dramatic changes was the accidental removal of an entire verse.

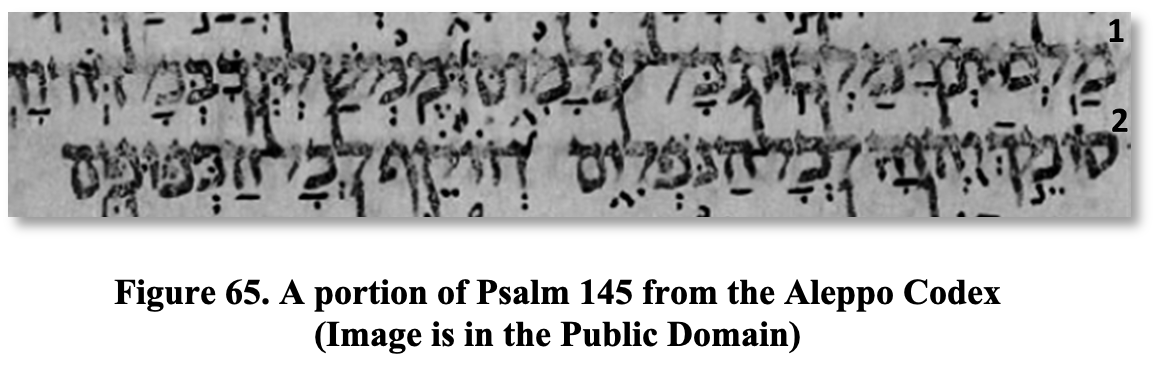

Psalm 145 is an acrostic psalm where each verse begins with successive letters of the Hebrew alphabet. In the Aleppo Codex, the first verse begins with the letter aleph, the second with the beyt, the third with the gimel, and so on. Verse 13 begins with the letter מ (mem), identified with the number “1” in Figure 65 above, the 13th letter of the Hebrew alphabet. The next verse in the image, identified with the number “2,” begins with the letter ס (samehh), the 15th letter of the Hebrew alphabet. There is no verse beginning with the 14th letter נ (nun).

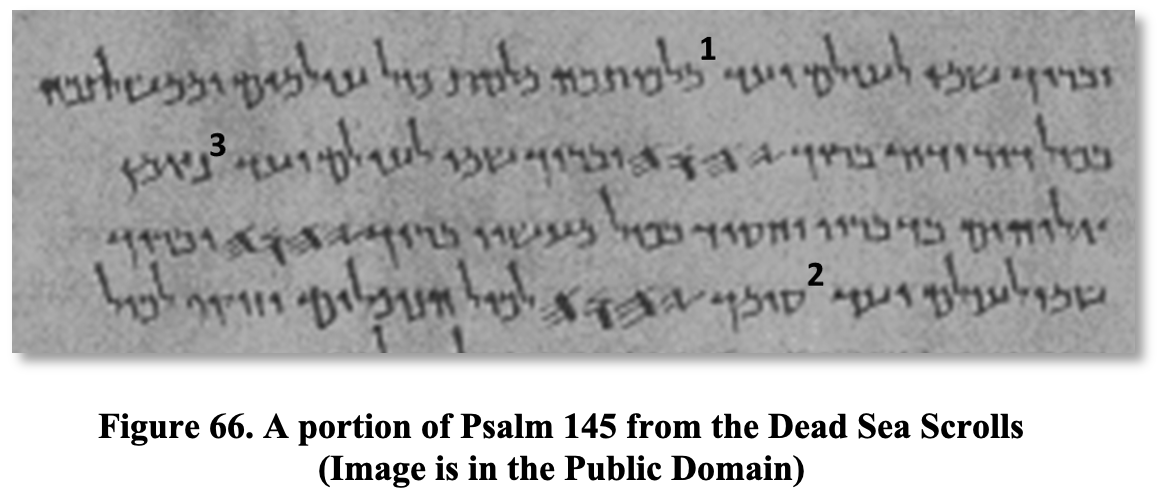

When we examine Psalm 145 from the Dead Sea Scrolls, we find between the verse beginning with the מ (mem), identified with a “1” in Figure 66 above, and the verse beginning with the ס (samehh), identified with a “2”, the missing verse, beginning with the letter נ (nun), is present and identified with a “3” and reads as follows:

נאמן אלוהים בדבריו וחסיד בכול מעשיו

This translates as:

“God is faithful in his words, and gracious in all his deeds.”

This is why Psalm 145:13 reads differently in the KJV compared with modern versions such as the RSV. The KJV was written prior to discovering the Dead Sea Scrolls, while the RSV and other modern versions were written afterward and often incorporate what has been found in the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Ancient Translations

As the Jewish people began to spread beyond Israel, they adopted the language of their new neighbors. This created the need for translations of the Bible into their assimilated languages so they could continue reading the Bible. While there have been translations of the Hebrew Bible into many different languages, the three most widely used in ancient times were the Latin, Aramaic and Greek translations.

Of the many Aramaic translations of the Hebrew Bible (see Figure 67), two are principal ones. Targum Onkelos is an Aramaic translation of the first five books of the Bible written in the 1st century AD by Onkelos, a Roman convert to Judaism. The second is the Targum Jonathan, an Aramaic translation of the prophets. It was written in the 1st century BC by Jonathan Ben Uziel, a student of Hillel the Elder, a famous Jewish teacher and religious leader.

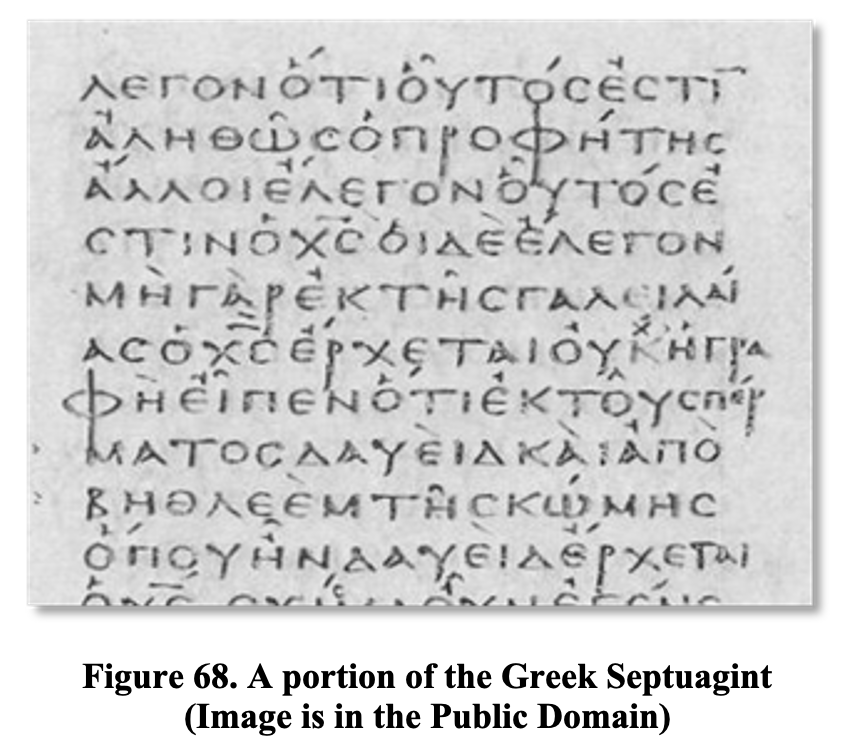

The Septuagint, the Greek translation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible (see Figure 68), was written by Jewish scholars in the 3rd century BC. The remainder of the Hebrew Bible, the writings and the prophets, was translated into Greek by unknown translators between the 2nd and 1st centuries BC.

The Latin Vulgate, comprised of the Hebrew Bible as well as the New Testament (see Figure 69), was translated by Jerome, a Christian priest and apologist, in the 5th century AD.

[1] The only exception is the Book of Esther, which has not been found in any of the Dead Sea Caves.